Finding brain tumours using image segmentation

Table of contents

This article goes through how to build an image segmentation model using the U-Net architecture, a state-of-the-art model used widely for medical processing of MRI scans. Image segmentation “colours” an image from a small number of colours, where each colour represents something. In our case, we will colour the tumour with white pixels, and non-tumorous pixels are coloured black.

Take a look at the final result on my GitHub, which includes a web app you can run on your local server!

Dataset and data processing

The dataset I used is from Kaggle, and can be found here. It consists of 3929 MRI scans and 3929 corresponding mask labels which show the true location of the tumour (if there is one at all). Here’s an example of one scan:

The goal of the model is to predict the mask (which has 1 channel) from the MRI scan (which has 3 channels).

The data is structured like so:

data

├── TCGA_CS_4941_19960909

│ ├── TCGA_CS_4941_19960909_1.tif

│ └── TCGA_CS_4941_19960909_1_mask.tif

│ └── ...

├── TCGA_CS_4941_19960908

│ ├── TCGA_CS_4941_19960908_1.tif

│ └── TCGA_CS_4941_19960908_1_mask.tif

│ └── ...

├── ...

We can use PyTorch to build a DataSet class that will automatically retrieve the images and their masks, and convert them to PyTorch tensors:

import torch as t

from torch.utils.data import Dataset

from torchvision import transforms

from PIL import Image

import os

class ImageMasksDataset(Dataset):

def __init__(self, root_dir, transform):

super().__init__()

self.root_dir = root_dir

self.transform = transform

# This will store tuples of (image_file_path, mask_file_path)

self.image_mask_pairs = []

# Iterate through all folders in the root directory (TCGA_CS_4941_19960909, TCGA_CS_4941_19960908...)

for folder in os.listdir(root_dir):

folder_path = os.path.join(root_dir, folder)

if os.path.isdir(folder_path):

# Locate all image files (NOT masks) and sort alphabetically

images = sorted([f for f in os.listdir(folder_path) if f.endswith(".tif") and "mask" not in f])

for img_file in images:

# Find the corresponding mask

mask_file = img_file.replace(".tif", "_mask.tif")

img_path = os.path.join(folder_path, img_file)

mask_path = os.path.join(folder_path, mask_file)

if os.path.exists(mask_path):

self.image_mask_pairs.append((img_path, mask_path))

def __len__(self):

return len(self.image_mask_pairs)

def __getitem__(self, idx):

# Get the filepaths

img_path, mask_path = self.image_mask_pairs[idx]

# Use PIL to open the image with the right number of channels (3 and 1 respectively)

img = Image.open(img_path).convert("RGB")

mask = Image.open(mask_path).convert("L")

# Apply transforms (ToTensor, Resize, etc.)

if self.transform:

img, mask = self.transform(img), self.transform(mask)

# Remove channel dimension from mask (as it is grayscale, 1 channel only)

mask = mask.squeeze(0)

# Ensure that mask is not of float dtype because this will cause issues with cross entropy loss later

return img, mask.to(t.long)

transform = transforms.Compose([

transforms.Resize((128,128)),

transforms.ToTensor(),

])

dataset = ImageMaskDataset("./data", transform)

Whenever we index the ImageMaskDataset, e.g. dataset[5], then the __getitem__ method is called. All the filepaths were found in the initialisation of dataset, so we can simply locate the filepaths from the self.image_mask_pairs List, open them using PIL.Image, and convert to tensors using torchvision transforms. Note: .ToTensor() normalises all the pixel values to be between 0 and 1. If you want to display the images later, you will have to multiply by 255.

We can use PyTorch’s random_split and DataLoader objects to split the dataset into training, validation, and testing sets, and convert to data loaders:

from torch.utils.data import

batch_size = 64

train_frac = 0.7

val_frac = 0.15

train_size = int(train_frac * len(dataset))

val_size = int(val_frac * len(dataset))

test_size = len(dataset) - train_size - val_size

train_set, val_set, test_set = random_split(dataset, lengths=[train_size, val_size, test_size])

train_loader = DataLoader(train_set, batch_size=batch_size, shuffle=True)

train_loader = DataLoader(val_set, batch_size=batch_size, shuffle=False)

train_loader = DataLoader(test_set, batch_size=batch_size, shuffle=False)

Model definition

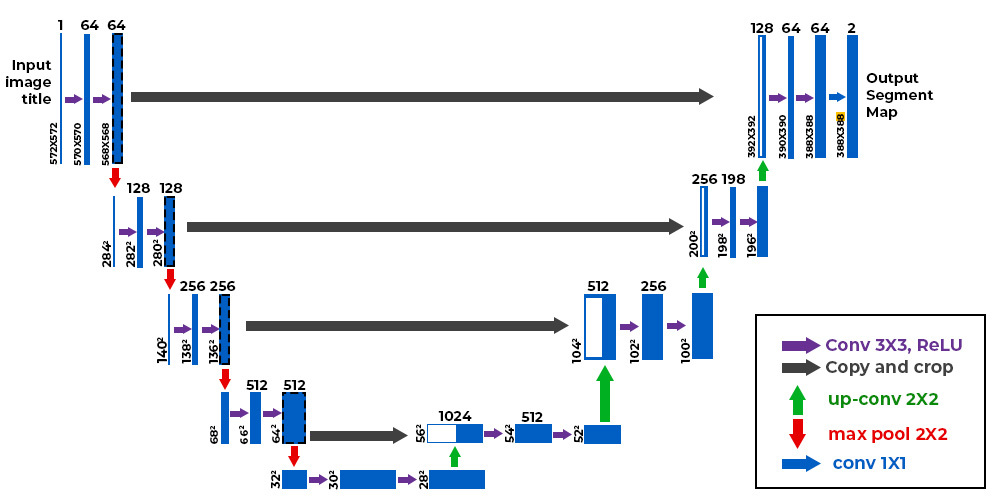

We will be using the U-Net architecture. It consists of three major parts: the encoder, the decoder, and the bottleneck.

The encoder is responsible for the following:

- Downsample (reduce the size of) the image using convolution layers

- Increase number of channels using convolution layers

Intuitively, downsampling and increasing the number of channels is converting an image to a set of features, such as “there is a tumour here”, or “there is no tumour here”. Incidentally, an image classifier model such as the ResNet only consists of an encoder - it uses convolutions to store features in the newly added channels, and reduces the image size until the image is a 1D vector that can be processed by a dense layer.

The decoder is responsible for the following:

- Given the low-size, high-channels image, upsample the image using bilinear interpolation. Essentially, the model increases the size of the image, and to determine what to put in the new pixels, it uses interpolation between the existing pixels in the image.

- Reduce the number of channels, eventually to the number of output channels. This “constructs” the mask.

The bottleneck is simply the connecting section between the encoder and decoder. It consists of convolutions that do not impact the image size, but may increase the number of channels further.

A unique feature of the U-Net is that it is symmetric, with connections between the encoding and decoding sections:

The diagram shows 4 encoding layers on the left, and 4 decoding layers on the right, with a bottleneck at the bottom. The encoding and decoding layers are arranged into pairs. The grey-arrow indicates a concatenation operation, which happens along the channel dimension. This is useful because intuitively, the decoding layer is locating features in the image at a range of image sizes (since it downsamples after each layer). For the encoding layer to construct the mask in the correct position, it needs to know where the decoder thought the tumour was. By concatenating the outputs of the corresponding decoding layer, the encoder can construct the tumour in the right position. Without this concatenation, the encoder would have no idea where to put the mask, since by the bottleneck layer, most of the spatial information in the image is gone, since it was downsampled to as small as 16 x 16!

Here is the code for the UNet class that I used:

from torch import nn

import nn.functional as F

class UNet(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, in_channels, out_channels):

super().__init__()

# Encoder blocks - increase num channels

self.enc1 = self.conv_block(in_channels, 64)

self.enc2 = self.conv_block(64, 128)

self.enc3 = self.conv_block(128, 256)

self.enc4 = self.conv_block(256, 512)

# Bottleneck - increase channels to maximum

self.bottleneck = self.conv_block(512, 1024)

# Decoder - reduce num channels and increase image size (upsample)

self.upconv4 = self.upconv(1024, 512)

self.dec4 = self.conv_block(1024, 512)

self.upconv3 = self.upconv(512, 256)

self.dec3 = self.conv_block(512, 256)

self.upconv2 = self.upconv(256, 128)

self.dec2 = self.conv_block(256, 128)

self.upconv1 = self.upconv(128, 64)

self.dec1 = self.conv_block(128, 64)

# Final 1x1 convolution

self.conv_last = nn.Conv2d(64, out_channels, kernel_size=1)

def conv_block(self, in_channels, out_channels):

# A layer consisting of two convolutions, with BatchNorm and ReLU

return nn.Sequential(

nn.Conv2d(in_channels, out_channels, kernel_size=3, padding=1),

nn.BatchNorm2d(out_channels),

nn.ReLU(inplace=True),

nn.Conv2d(out_channels, out_channels, kernel_size=3, padding=1),

nn.BatchNorm2d(out_channels),

nn.ReLU(inplace=True),

nn.Identity() # Optional skip connection

)

def upconv(self, in_channels, out_channels):

# Upsample - increase image size and reduce num channels

return nn.Sequential(

nn.Upsample(scale_factor=2, mode="bilinear", align_corners=True),

nn.Conv2d(in_channels, out_channels, kernel_size=3, padding=1),

)

def forward(self, x):

# Encoding - MaxPooling is used to reduce the image size

enc1 = self.enc1(x)

enc2 = self.enc2(F.max_pool2d(enc1, kernel_size=2))

enc3 = self.enc3(F.max_pool2d(enc2, kernel_size=2))

enc4 = self.enc4(F.max_pool2d(enc3, kernel_size=2))

# Bottlenecking

bottleneck = self.bottleneck(F.max_pool2d(enc4, kernel_size=2))

# Decoding - first upsample, then concatenate the corresponding encoding output, and then reduce channels

dec4 = self.upconv4(bottleneck)

dec4 = t.cat((enc4, dec4), dim=1)

dec4 = self.dec4(dec4)

dec3 = self.upconv3(dec4)

dec3 = t.cat((enc3, dec3), dim=1)

dec3 = self.dec3(dec3)

dec2 = self.upconv2(dec3)

dec2 = t.cat((enc2, dec2), dim=1)

dec2 = self.dec2(dec2)

dec1 = self.upconv1(dec2)

dec1 = t.cat((enc1, dec1), dim=1)

dec1 = self.dec1(dec1)

return self.conv_last(dec1)

model = UNet(in_channels=3, out_channels=2)

A few notes:

- The

self.encandself.decattributes themselves do not downsample or upsample - they only change the number of channels, sinceself.conv_block()does not change image size. - Upsampling is done using

upconv. Downsampling is done usingMaxPool2D. MaxPooling simply assigns the maximum value within the kernel to each pixel (unlike Conv2d which takes a weighted sum over the kernel). - You might be confused as to why we have 2 output channels and not 1 for a grayscale image. Later, we are going to use

CrossEntropyLossby treating each pixel as a probability distribution. The distribution has two classes - tumorous (index 1) and non-tumorous (0), so we need 2 output channels.

Model training

Our loss function is the cross entropy loss between each pixels probability distribution and the target distribution. For example, a certain pixel may have a distribution of [0.2, 0.8], meaning the model thinks there is a 80% chance the pixel is part of a tumour, and 20% chance it is not. If the pixel was actually tumorous, the target distribution would be [0, 1].

lr = 1e-03

wd = 1e-03

class_weights = t.tensor([0.2, 0.8]).to(device)

criterion = nn.CrossEntropyLoss(weight=class_weights)

optimizer = t.optim.AdamW(model.parameters(), lr=lr, weight_decay=wd)

You’ll notice I passed in a class_weights tensor into nn.CrossEntropyLoss. This modifies the standard cross entropy formula - if the correct class is at index i, then we multiply the negative log likelihood by the corresponding class weight. In this case, I’ve chosen to penalise the model more heavily if it predicts a tumorous pixel as non-tumorous. This is because for almost every image, the majority of the pixels in the mask are non-tumorous, which could incentivise the model to just predict everything as non-tumorous to get artifically low loss.

I’m using the Adam optimiser with a small amount of weight decay to add L2 regularisation, which will prevent overfitting (hopefully).

Use these helper functions for training and validation. train_one_epoch iterates through the data loader, and for each batch, computes the model predictions and the associated loss from the true masks, backpropagates to find gradients, and performs one step of gradient descent using Adam.

from tqdm import tqdm # For aesthetic progress bars

def train_one_epoch(model, train_loader, criterion, optimizer, device):

total_loss = 0

for inputs, labels in tqdm(train_loader):

inputs, labels = inputs.to(device), labels.to(device)

logits = model(inputs)

loss = criterion(logits, labels)

total_loss += loss.item()

loss.backward()

optimizer.step()

optimizer.zero_grad()

return total_loss / len(train_loader)

def eval(model, val_loader, criterion, device):

model.eval()

total_loss = 0

with t.no_grad():

for inputs, labels in tqdm(val_loader):

inputs, labels = inputs.to(device), labels.to(device)

logits = model(inputs)

loss = criterion(logits, labels)

total_loss += loss.item()

return total_loss / len(val_loader)

Now let’s run the training loop for 10 epochs (you can do more if you like, but I found there was little improvement in validation loss beyond 10 epochs):

train_losses = []

val_losses = []

num_epochs = 10

for epoch in range(1, num_epochs+1):

train_loss = train_one_epoch(model, train_loader, criterion, optimizer, device)

val_loss = eval(model, val_loader, criterion, device)

train_losses.append(train_loss)

val_losses.append(val_loss)

print(f"Epoch {epoch}/{num_epochs} | Train loss : {train_loss:.3e} | Val loss : {val_loss:.3e}")

My loss evolution plot looked like this with a minimum validation loss of around 3.6e-02:

Making predictions

That concludes the training of the model! Now we can test the model out on unseen samples, and see how it fares.

Here’s a small function I wrote for displaying an MRI scan, the predicted mask, and the model’s prediction of the mask:

def compare_model_label(idx):

image = test_set[idx][0].unsqueeze(0).to(device)

with t.no_grad():

pred = model(image).squeeze(0).argmax(dim=0)

pred_img = (pred.cpu().detach().numpy() * 255).astype(np.uint8)

label = train_set[idx][1]

label_img = (label.cpu().numpy() * 255).astype(np.uint8)

image = train_set[idx][0]

image = (image.permute(1,2,0).numpy()*255).astype(np.uint8)

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 3, figsize=(15, 5))

axes[0].imshow(image)

axes[0].axis("off")

axes[0].set_title("Scan")

axes[1].imshow(label_img, cmap="gray")

axes[1].axis("off")

axes[1].set_title("Actual Mask")

axes[2].imshow(pred_img, cmap="gray")

axes[2].axis("off")

axes[2].set_title("Predicted Mask")

plt.show()

Note: you need to add a batch dimension using .unsqueeze(0) to run a single sample through the model. You then need to remove the batch dimension using .squeeze(0) because matplotlib.pyplot won’t display it otherwise. Remember that in converting the raw samples to tensors, the values were normalised to be between 0 and 1, so you need to multiply by 255. Furthermore, matplotlib.pyplot expects images to have shape (H, W, C) (height, width, channels). Since our model was designed to accept (C, H, W), you need to permute the dimensions. This can be done by doing .permute(1, 2, 0) - the original dimensions were (0, 1, 2), and by permuting to (1, 2, 0), you put the first dimension in last place, and move the last two dimensions to the front.

Running the function on a random sample from the test set, I get:

The results are pretty good!

Conclusion

In this article, I went through data processing with images using a PyTorch Dataset, walked you through the U-Net architecture, and showed the results from a trained model, which are quite impressive, and have the potential to improve the efficiency of patient diagnoses in a positive way.