Transformers: theory and implementation

Table of contents

- What does a transformer do?

- Tokenisation

- Embedding

- The residual stream

- Attention layer

- MLP

- Putting it all together

- Loss functions

- Conclusion and key takeaways

- Credits

The Transformer model has revolutionised how we approach natural language processing (NLP). First introduced in the groundbreaking paper “Attention is All You Need”, by Vaswani et al., transformers have become one of the hottest research topics in AI.

A transformer consists of the following parts: embedding, positional embedding, attention layers, MLP layers, and a de-embedding layer, with all processing done in the residual stream. This article aims to provide a theoretical summary of transformers, alongside Python implemenations for each of these layers, culminating in a Transformer class that can succesfully predict text!

What does a transformer do?

Transformers try to predict text. More formally, if we give a transformer a sequence of \(n\) words, it returns a probability distribution over all the possible words in the English dictionary. We can then select the word with the highest probability as our \(n+1\)th word.

Tokenisation

A string of text is not something a neural network can easily process. Neural networks use matrix multiplication operations, and so ideally we want to represent our input data as a tensor. Our starting point is a vocabulary which contains all the possible words we are using in our model. This may possibly be the English dictionary. We give each unique word an index using a Python dictionary data structure (hash map). As an example, suppose this was our dictionary:

vocab = {0: "apple", 1: "banana", 2: "orange"}

Then, the following string: input_sequence = "banana orange apple" could be re-expressed as a vector like tokens = [1, 2, 0]. These numerical values are called tokens.

We can do better than this, though. One-hot encoding is a method of uniquely identifying elements in a dictionary by setting all indices in a vector of size \(1 \times vocab \_size \) to zeroes, apart from the index corresponding to the word that is present. So, banana, would be the same as this vector: [0, 1, 0]. And our sentence is now a matrix:

[[0, 1, 0], #1: banana

[0, 0, 1], #2: orange

[1, 0, 0]] #0: apple

In practice tokens are not actually words, but rather common combinations of characters. Our dictionary of tokens may be ordered from the most common tokens (perhaps ‘at’, ‘he’, ‘ing’ - phonetic sounds common in many words) to the least common tokens (such as ‘aardvark’, say).

Embedding

Tokenisation is fine. But remember that the English language has approximately 170,000 words in current use. Even with our tokenising stategy, that means we are working in a space with a number of dimensions on the order of tens of thousands at least.

One hot encoding essentially turns each token in the vocabulary into a standard basis vector. For example, if we had three tokens, this would be a 3D space with each one hot encoded token vector being mutually orthogonal to each other.

Instead, let’s trying multiply our vector of size vocab_size with a matrix of size vocab_size * d_model. This produces a vector of size d_model. What we’ve done here is project our vocab_size dimensional vector onto a d_model dimensional space. d_model is 764 in GPT-2. Mathematically, this operation can be expressed as follows:

\[x_E = x W_E \]

where \(x_E\) is a matrix of size seq_len * d_model (embedded token vectors, with each row representing one embedded token), \(x\) is a matrix of size seq_len * vocab_size, and \(W_E\) is the embedding matrix which has size vocab_size * d_model.

The crucial part about embedding is that it reduces the number of dimensions we’re working with. The values in \(W_E\) are found by backpropagation during training. A good embedding matrix will group tokens with similar meanings or contexts together.

Here’s a possible implementation of an Embedding class:

class Embed(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, cfg: Config):

super().__init__()

self.cfg = cfg

self.W_E = nn.Parameter(t.empty((cfg.d_vocab, cfg.d_model)))

nn.init.normal_(self.W_E, std=self.cfg.init_range)

def forward(self, tokens: Int[Tensor, "batch position"]) -> Float[Tensor, "batch position d_model"]:

return self.W_E[tokens]

This class inherits the Config class:

@dataclass

class Config:

d_model: int = 768 # N-dims of residual stream

debug: bool = True # Debug mode

layer_norm_eps: float = 1e-5 # Used in LayerNorm class

d_vocab: int = 50257 # Vocab size

init_range: float = 0.02 # For random init

n_ctx: int = 1024 # Longest seq len

d_head: int = 64 # N-dims of attention head

d_mlp: int = 3072 # N-dims of MLP layer

n_heads: int = 12 # No. of att. heads / layer

n_layers: int = 12 # No. of att. + MLP blocks

In the Embedding class, we specify the \(W_E\) matrix in the constructor to be set to values taken from a standard normal distribution. Then, in the forward function, we simply extract the embedded vectors for each token value. For example, if the token is 5, we extract self.W_E[5]. The results are stacked together, so we get a matrix of size seq_len * d_model.

Positional embedding

While standard embedding encodes based on the token id, positional embedding does exactly what the name implies: it encodes the positional data of each token. Here’s a quick implementation of a PosEmbed class:

class PosEmbed(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, cfg: Config):

super().__init__()

self.cfg = cfg

self.W_pos = nn.Parameter(t.empty((cfg.n_ctx, cfg.d_model)))

nn.init.normal_(self.W_pos, std=self.cfg.init_range)

def forward(self, tokens: Int[Tensor, "batch position"]) -> Float[Tensor, "batch position d_model"]:

#use einops repeat

batch, seq_len = tokens.shape

return einops.repeat(self.W_pos[:seq_len], "posn d_model -> batch posn d_model", batch=batch)

The residual stream

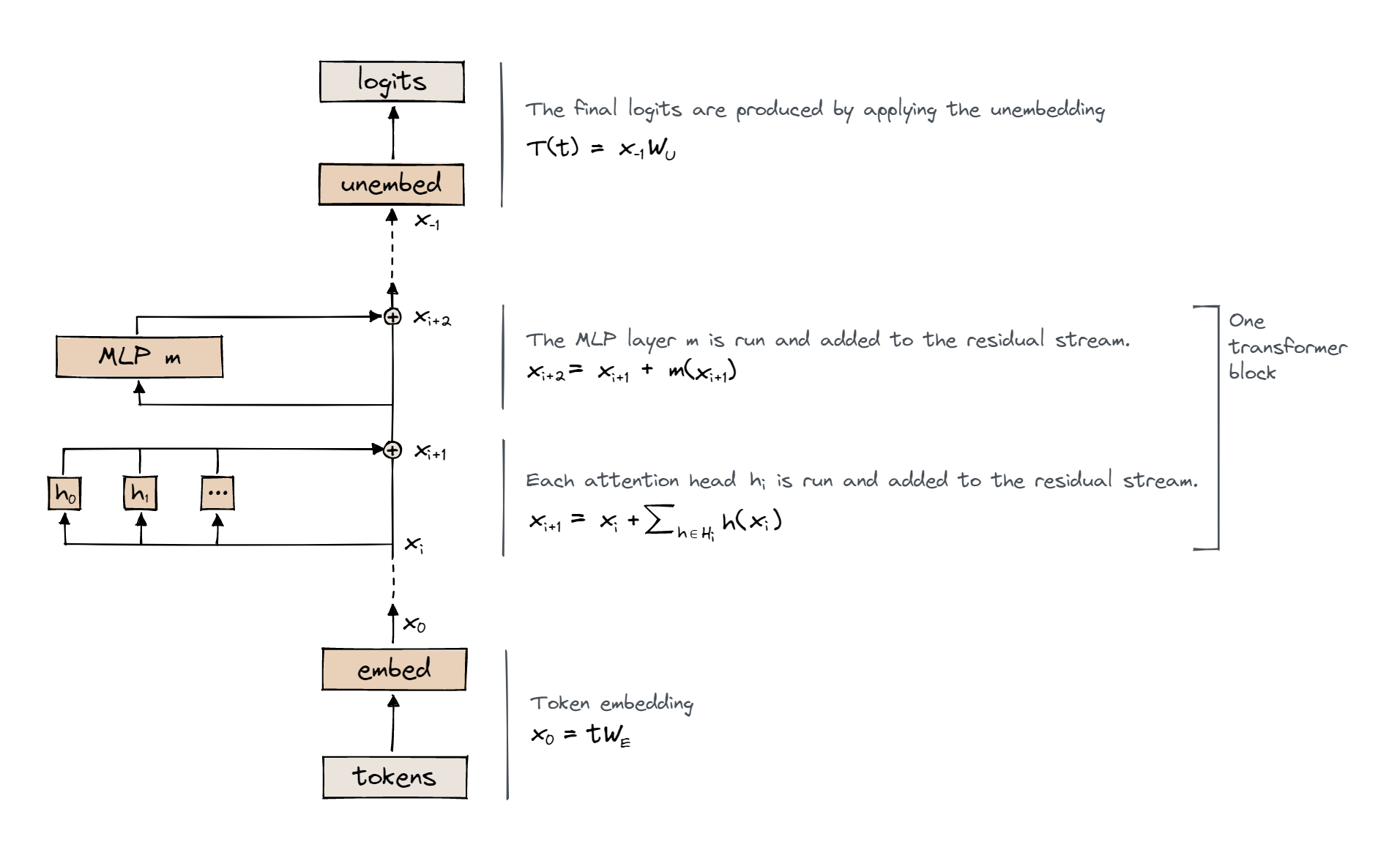

Before continuing onto the attention layer, I think its important that we talk about what the residual stream is. Once the sequence is embedded it now lives in the residual stream. This can be thought of as a d_model dimensional space in which the embedded tokens are gradually processed. Consider the diagram below:

The residual stream is the long line spanning the embed and unembed. After each layer (e.g. attention, MLP), we add the result of that layer, plus the original value of the residual stream vectors, before applying the layers. Importantly, the residual stream is a temporary working space for the transformer to perform operations on the input data.

Attention layer

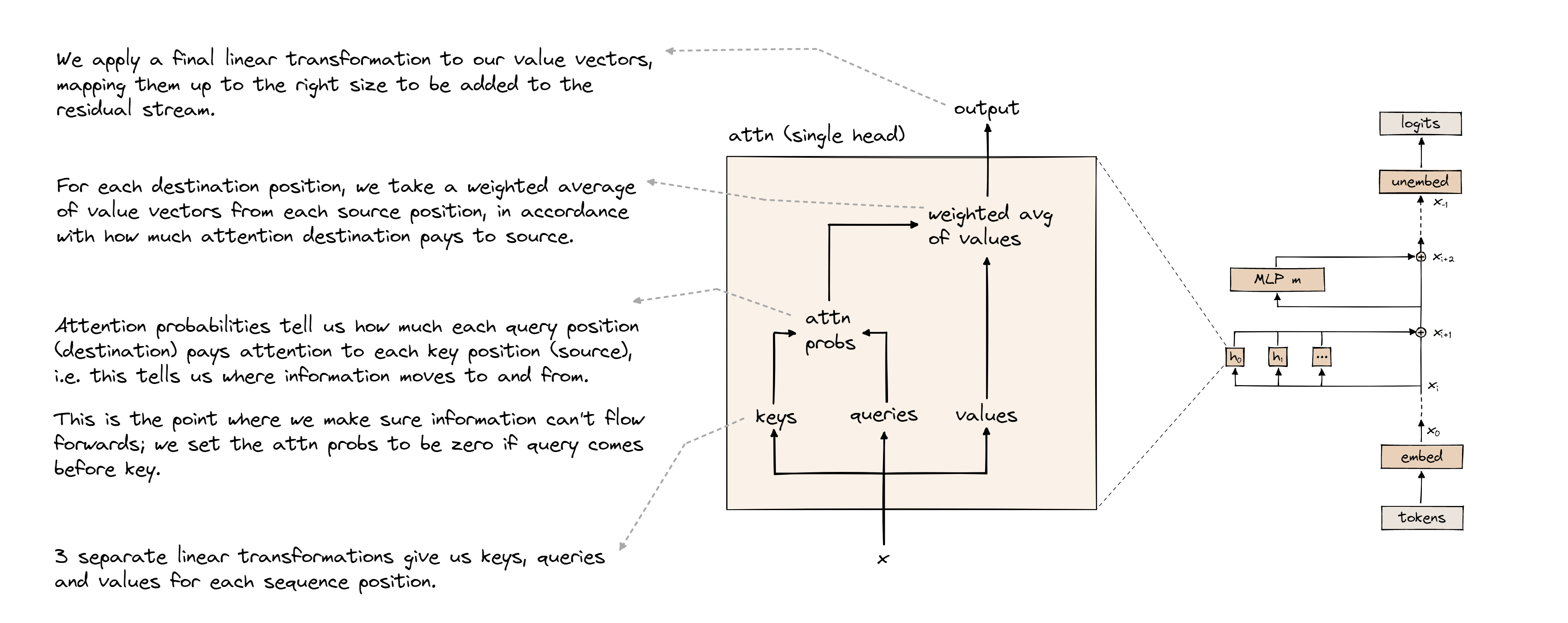

This is arguably the most crucial layer in the transformer. Looking at the transformer diagram from earlier, we can see there are n_heads attention heads in one attention layer. To begin, we can think of attention as a mechanism that moves information between tokens, depending on how useful that information is for predicting the next token. Take a look at the following diagram of an attention head:

We begin by multiplying the residual stream vector \(x\) by the following matrices: \(W_K\), \(W_Q\), and \(W_V\) and adding the biases \(b_K\), \(b_Q\), \(b_V\), to compute the keys \(k\), the queries \(q\), and the values \(v\) respectively. Notice how multiplying \(x\) (shape: seq_len * d_model) with each of these matrices (all have same shape: d_model * d_head) collapses the residual stream down to d_head dimensions instead of d_model dimensions. Reduced dimensions reduces the computational complexity of applying attention to the residual stream.

Now, let’s conceptually dive into queries, keys, and values. A query can be thought of as the current token asking a “question”, which is, generally speaking, something like: “How am I related to other words in the sentence?”. For example, suppose we had the sentence “The cat sat on the mat”. The token “sat” might ask a question like - “what thing is related to my action?”. And “cat” might offer an answer (key) like, “I am the object associated with sat”. Consequently, we give “cat” a high weighting to the interaction between “cat” and “sat”, because their query and key form a good question-answer pair. So a query is just a question, and a key is just a possible answer to that question.

There’s a useful analogy here between convolutions and attention. In a CNN, we exploit the fact that pixels close together share useful information. Imagine you were given a single pixel of an image, and asked to identify what the image was. Intuitively, you would want to search the surrounding pixels, rather than looking for a random pixel on the other side of the image. Similarly, attention can be viewed as training the model to identify which tokens share information with each other.

Back to the math. To assess the match of a query and key, we do the following:

\[a = qk^T\]

where \(a\) represents attention probabilities, \(q\) represents the matrix of queries for each token, and \(k^T\) is just the transpose of the key matrix.

Multiplying the queries (shape: seq_len * d_head) by transposed keys (shape: d_head * seq_len) can be interpreted as dot producting each query row (for each token) with each key column. So for some tokens \(i\) and \(j\) we compute this dot product over all \(i, j\). The nice thing about a dot product is that it tells you how similar two vectors are. So if we get a large value in our dot product, we interpret this as the query and key ‘matching’. The resulting matrix is a precursor to what will form the attention pattern matrix.

There’s a couple of cleanup tasks that we need to do. Firstly, we need to apply a causal mask to the attention pattern. What this means is forbidding attention to be paid between a token and one that appears in the future. The reason for this is simple: given some token, we want to prevent it from simply ‘cheating’ and looking at the token in front of itself. Secondly, we need to apply a softmax function to every row of the attention pattern. Here is the softmax function:

\[ \text{softmax}(\mathbf{x})_i = \frac{e^{x_i}}{\sum_{j=1}^{K} e^{x_j}} \]

It calculates the weighted exponential probability of a value \(x_i\). The intuition for softmax comes from the exponential - small differences in attention are amplified, allowing us to clearly see which token is the best to pay attention to; this is useful when attention values are very similar to each other.

Everything we have described so far forms the QK circuit of an attention head. Now let’s look at the OV circuit. Our masked, softmaxed attention matrix only tells us which tokens share mutual information. But, crucially, we also need a way for information to be copied between tokens. For example, consider the phrase “James Bond”. These tokens probably commonly occur next to each other. So in our attention pattern, we’d expect “Bond” to attend highly to “James”. The OV circuit therefore copies the token “James” into the residual stream of “Bond”.

Recall that we computed \( v = x W_v \). These are the values, and they tell us what information to copy from each token in the attention matrix. So, we know what information to copy from each token, and we know how much attention to pay to each token. So, naturally, we take a weighted sum of the values and the attention pattern. Finally, we multiply the result by \( W_O \) (shape: d_head * d_model). As you can see from its shape, the purpose of this matrix is to transform back into the residual stream space, since we contracted our dimensions to d_head inside the attention head.

In summary, the result of the QK circuit is:

\[ A = \text{softmax} \left( \frac{x^T W_Q W_K^T x}{\sqrt{d_{\text{head}}}} \right) \]

And the result of the OV circuit is:

\[ x_{i+1} = A v W_O \]

Here’s an implementation of the Attention class:

class Attention(nn.Module):

IGNORE: Float[Tensor, ""]

def __init__(self, cfg: Config):

super().__init__()

self.cfg = cfg

self.W_Q = nn.Parameter(t.empty((cfg.n_heads, cfg.d_model, cfg.d_head)))

self.W_K = nn.Parameter(t.empty((cfg.n_heads, cfg.d_model, cfg.d_head)))

self.W_V = nn.Parameter(t.empty((cfg.n_heads, cfg.d_model, cfg.d_head)))

self.W_O = nn.Parameter(t.empty((cfg.n_heads, cfg.d_head, cfg.d_model)))

self.b_Q = nn.Parameter(t.zeros((cfg.n_heads, cfg.d_head)))

self.b_K = nn.Parameter(t.zeros((cfg.n_heads, cfg.d_head)))

self.b_V = nn.Parameter(t.zeros((cfg.n_heads, cfg.d_head)))

self.b_O = nn.Parameter(t.zeros((cfg.d_model)))

nn.init.normal_(self.W_Q, std=self.cfg.init_range)

nn.init.normal_(self.W_K, std=self.cfg.init_range)

nn.init.normal_(self.W_V, std=self.cfg.init_range)

nn.init.normal_(self.W_O, std=self.cfg.init_range)

self.register_buffer("IGNORE", t.tensor(-1e5, dtype=t.float32, device=device))

def forward(self, normalized_resid_pre: Float[Tensor, "batch posn d_model"]) -> Float[Tensor, "batch posn d_model"]:

q = einops.einsum(normalized_resid_pre, self.W_Q, 'batch posn d_model, n_heads d_model d_head -> batch posn n_heads d_head') + self.b_Q

k = einops.einsum(normalized_resid_pre, self.W_K, 'batch posn d_model, n_heads d_model d_head -> batch posn n_heads d_head') + self.b_K

v = einops.einsum(normalized_resid_pre, self.W_V, 'batch posn d_model, n_heads d_model d_head -> batch posn n_heads d_head') + self.b_V

attn_scores = einops.einsum(q, k, 'batch posn_q n_heads d_head, batch posn_k n_heads d_head -> batch n_heads posn_q posn_k')

attn_scores = self.apply_causal_mask(attn_scores)

A = t.nn.functional.softmax(attn_scores / math.sqrt(self.cfg.d_head), dim = -1)

z = einops.einsum(v, A, 'batch posn_k n_heads d_head, batch n_heads posn_q posn_k -> batch posn_q n_heads d_head')

attn_pattern = einops.einsum(z, self.W_O, 'batch posn_q n_heads d_head, n_heads d_head d_model -> batch posn_q d_model') + self.b_O

return attn_pattern

def apply_causal_mask(self, attn_scores: Float[Tensor, "batch n_heads query_pos key_pos"]) -> Float[Tensor, "batch n_heads query_pos key_pos"]:

mask = t.triu(t.ones_like(attn_scores) * self.IGNORE, diagonal=1)

return mask + attn_scores

In the intitialiser, we define the query, key, value, and object weights and biases. Then, in the forward method, we take in the residual stream, and compute q, k, v. A couple of things to note here:

- We’re using

einopshere, a very powerful library for performing tensor multiplications. - We have an extra dimension called

batch. This is simply packaging multiple sequences of input into one big tensor. - We use a variable called

IGNORE. This is a massive negative number used to set all future attention values to effectively-inf, as part of the causal mask to prevent the model from cheating by looking into the future. After softmaxing, these probabilities become zero, which is the desired effect.

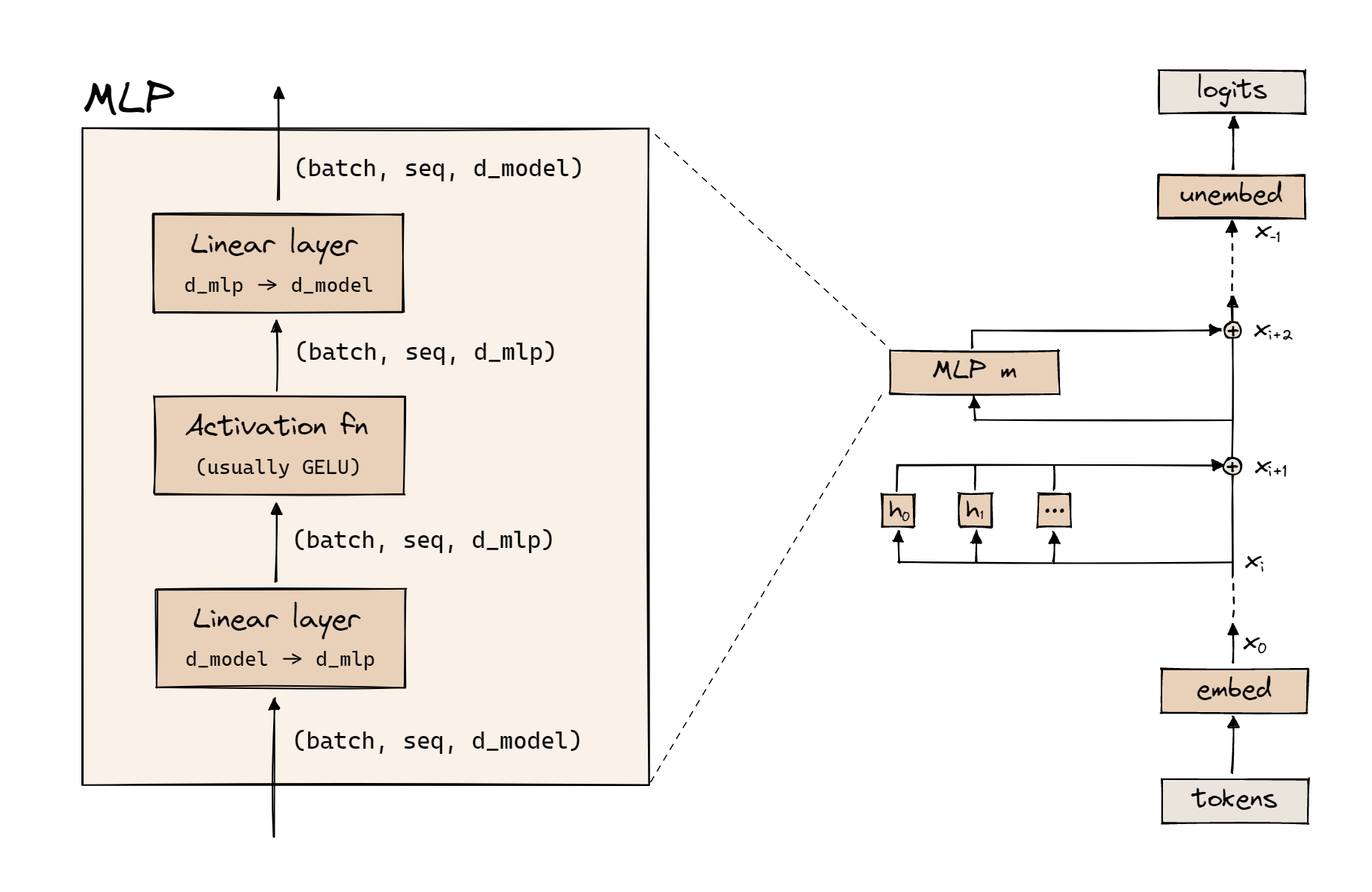

MLP

The multilayer perceptron (MLP) layer is a traditional dense neural network, with exactly one hidden layer. A diagram of the MLP layer is shown below:

First, we apply a linear transformation, which takes us from seq_len * d_model to seq_len * d_mlp:

\[x_1 = x_0 W_{in} + b_{in}\]

Then we apply an activation, usually <a href=https://www.mathworks.com/help/deeplearning/ref/dlarray.gelu.html>GELU</a>. Finally, we apply another linear transformation to convert back into d_model space:

\[x_2 = x_1 W_{out} + b_{out}\]

It’s slightly unclear what exactly MLPs are doing, but the following intuition might help: attention identifies weightings for inter-token relationships, whilst the MLP allows non-linear features to be captured in the residual stream on each of the tokens individually. Without an MLP, high-level features such as tone and grammar would be missing.

Putting it all together

We now have the foundational components for our transformer! A transformer consists of multiple transformer blocks or transformer layers. Unhelpfully, one transformer layer actually has two layers: an attention layer and an MLP layer. Below is an implenentation for a TransformerBlock class:

class TransformerBlock(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, cfg: Config):

super().__init__()

self.cfg = cfg

self.ln1 = LayerNorm(cfg)

self.attn = Attention(cfg)

self.ln2 = LayerNorm(cfg)

self.mlp = MLP(cfg)

def forward(

self, resid_pre: Float[Tensor, "batch position d_model"]

) -> Float[Tensor, "batch position d_model"]:

resid_mid = self.attn.forward(self.ln1.forward(resid_pre)) + resid_pre

resid_post = self.mlp.forward(self.ln2.forward(resid_mid)) + resid_mid

return resid_post

rand_float_test(TransformerBlock, [2, 4, 768])

load_gpt2_test(TransformerBlock, reference_gpt2.blocks[0], cache["resid_pre", 0])

You might notice this class uses the LayerNorm class, which we haven’t discussed yet. All LayerNorm does is normalise the values in the residual stream after positional embedding, and applying a linear transformation. See the PyTorch documentation for more details.

Here’s a quick implementation of LayerNorm:

class LayerNorm(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, cfg: Config):

super().__init__()

self.cfg = cfg

self.w = nn.Parameter(t.ones(cfg.d_model))

self.b = nn.Parameter(t.zeros(cfg.d_model))

def forward(self, residual: Float[Tensor, "batch posn d_model"]) -> Float[Tensor, "batch posn d_model"]:

mean = t.mean(residual, dim=-1, keepdim=True)

var = t.var(residual, dim=-1, correction=0, keepdim=True)

residual -= mean

residual /= t.sqrt(var + self.cfg.layer_norm_eps)

residual = residual*self.w + self.b

return residual

Finally, we apply a linear transformation in the Unembed class, which transforms us back into seq_len * vocab_size space:

class Unembed(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, cfg):

super().__init__()

self.cfg = cfg

self.W_U = nn.Parameter(t.empty((cfg.d_model, cfg.d_vocab)))

nn.init.normal_(self.W_U, std=self.cfg.init_range)

self.b_U = nn.Parameter(t.zeros((cfg.d_vocab), requires_grad=False))

def forward(

self, normalized_resid_final: Float[Tensor, "batch position d_model"]

) -> Float[Tensor, "batch position d_vocab"]:

out = einops.einsum(self.W_U, normalized_resid_final, 'd_model d_vocab, batch posn d_model -> batch posn d_vocab') + self.b_U

return out

We’re now finally in a position to assemble the whole transformer! Remember, this is the order of operations: embedding, positional embedding, then \(n \) transformer layers (each with an attention layer and MLP layer), and finally, unembedding. (we also apply LayerNorm prior to each transformer block)

Here’s our final class, DemoTransformer:

class DemoTransformer(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, cfg: Config):

super().__init__()

self.cfg = cfg

self.embed = Embed(cfg)

self.pos_embed = PosEmbed(cfg)

self.blocks = nn.ModuleList([TransformerBlock(cfg) for _ in range(cfg.n_layers)])

self.ln_final = LayerNorm(cfg)

self.unembed = Unembed(cfg)

def forward(self, tokens: Int[Tensor, "batch position"]) -> Float[Tensor, "batch position d_vocab"]:

x = self.embed(tokens) + self.pos_embed(tokens)

for transformerBlock in self.blocks:

x = transformerBlock(x)

return self.unembed(self.ln_final(x))

Loss functions

The implementation of our transformer is complete. To train it, we will of course need a loss function:

\[ H(p, q) = -\sum_{x} p(x) \log q(x) \tag{1}\]

\[ D_{KL}(p \parallel q) = \sum_{x} p(x) \log\left(\frac{p(x)}{q(x)}\right) \tag{2}\]

\[D_{KL}(p \parallel q) = H(p, q) - H(p) \tag{3}\]

Equation \((1)\) is the cross entropy loss between two distributions, \( p(x) \) (true distribution) and \( q(x) \) (predicted distribution). In our case, the true probability distribution is 0 for all tokens except the correct token. So the loss function collapses to:

\[ -log(q(x)) \tag{4}\]

The KL divergence is closely related to the cross-entropy loss, and is described in equation \((2)\). The relationship between cross-entropy and KL divergence is shown in equation \((3)\).

Conclusion and key takeaways

In this article, we discussed the fundamental building blocks of a transformer. Here are some key takeaways:

- Transformers produce a probability distribution for the token at position \(i+1\), given a token at position \(i\).

- Tokens are embedded to reduce dimensions and group similar tokens together.

- Attention is used to capture pairwise relationships between tokens, through an attention matrix. This is done by asking questions (queries), and testing the match of answers (keys).

- The MLP layer independently operates on each token. It applies non-linear transformations to the tokens.

We also looked at coding implementations of relevant classes - Attention, MLP, Embed, etc. This mainly involved using class inheritance and tensor multplication using the einops library.

In the next article on transformers, we’ll be looking at mechanistic interpretability of transformers, and using Neel Nanda’s TransformerLens library! See you there!

Credits

The codes in this article are based on Callum McDougall’s excellent exercises for ARENA, an ML/AI safety bootcamp.